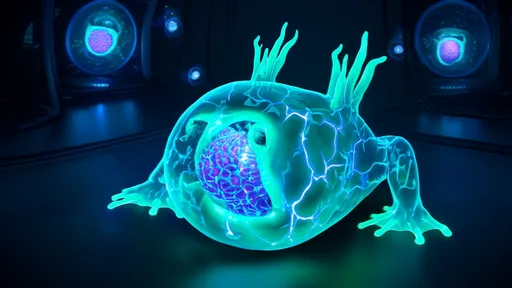

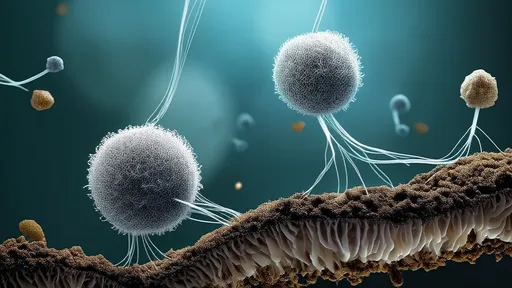

In a groundbreaking leap for regenerative biology, scientists have successfully created living robots—known as xenobots—from reprogrammed frog cells. These tiny, self-healing organisms, measuring less than a millimeter wide, blur the line between traditional robotics and organic life. Unlike conventional machines, xenobots are neither metal nor plastic but living entities designed by algorithms and assembled from biological tissue. Their creation opens a new frontier in medicine, environmental science, and our understanding of life itself.

The xenobots are crafted from the skin and heart cells of the African clawed frog (Xenopus laevis), hence their name. Researchers at Tufts University and the University of Vermont used a supercomputer to simulate thousands of potential cell configurations, selecting designs that could perform simple tasks like pushing microscopic payloads or navigating aqueous environments. The most promising blueprints were then brought to life by manually assembling frog cells under a microscope. Remarkably, these cell clusters began working together as cohesive units, exhibiting behaviors not seen in nature.

What sets xenobots apart is their capacity for self-regeneration. When sliced in half, some xenobots can stitch themselves back together within minutes—a feat impossible for any machine made of steel or silicon. This ability stems from their biological composition; the frog cells retain their innate capacity to adhere and reorganize. Such resilience hints at future applications in regenerative medicine, where similar bio-robots could repair damaged tissues or deliver drugs with unprecedented precision.

Ethical questions, however, loom large. While xenobots lack nervous systems or reproductive organs, their existence challenges definitions of life and autonomy. Critics argue that manipulating living cells for human-designed purposes ventures into morally ambiguous territory. Proponents counter that xenobots are simply sophisticated tools, no more sentient than lab-grown skin grafts. The debate underscores the need for frameworks to govern this emerging field before it outpaces societal consensus.

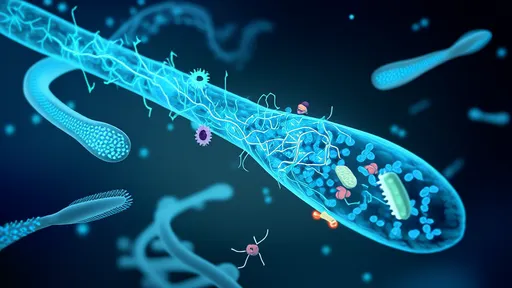

Beyond medicine, xenobots may revolutionize environmental remediation. Early experiments show they can autonomously gather microplastics in water or disperse beneficial microbes in contaminated soil. Their biodegradable nature ensures they won’t persist like synthetic pollutants. Still, scalability remains a hurdle. Current xenobots survive for only weeks before their cells naturally break down, though future iterations could be engineered for longer lifespans or targeted decomposition.

The team behind xenobots emphasizes that these are not genetically modified organisms (GMOs). No DNA was altered; instead, existing cells were rearranged into novel configurations. This distinction is crucial for regulatory approval and public acceptance. Yet the technology’s potential to evolve is undeniable. Future designs might incorporate cells from other species, enabling functionalities like photosynthesis or toxin resistance—imagine solar-powered bio-robots cleaning oil spills.

Perhaps the most profound implication lies in what xenobots reveal about life’s plasticity. Their existence suggests that complex behaviors can emerge from simple cell groupings without centralized control, echoing theories about the origins of multicellular life. By reverse-engineering such processes, scientists edge closer to answering existential questions: What defines an organism? How do cells "decide" to collaborate? Each xenobot, in its silent swimming, carries whispers of biology’s deepest mysteries.

As research accelerates, collaborations are forming between developmental biologists, roboticists, and ethicists. Military agencies have expressed interest—the Pentagon’s DARPA has funded related work—raising concerns about weaponization. Meanwhile, open-source platforms allow citizen scientists to simulate xenobot designs, democratizing access while amplifying risks. The balance between innovation and oversight will shape whether this technology heals or harms.

For now, xenobots exist primarily in petri dishes, their movements choreographed by the pulse of heart cells. But their legacy may be monumental: proof that life’s building blocks can be harnessed without domination, that machines need not be cold and unfeeling. In these flecks of frog tissue, we glimpse a future where biology and technology merge—not as master and slave, but as partners in reinventing life.

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025

By /Jul 3, 2025